Tuesday, October 30, 2018

Friday, October 26, 2018

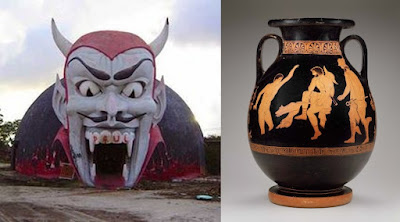

Haunted Texts and Philo-xeni Archaeology

“Stories of a visit to the realm of the dead and a return to the upper world are among the oldest narratives in European culture, beginning with Homer’s Odyssey and extending to contemporary fiction and art. Judith Fletcher examines a variety of different genres by twentieth- and twenty-first-century authors and artists, including Salman Rushdie, Neil Gaiman, Elena Ferrante, and Anish Kapoor, who deal in various ways with the descent to Hades in literary fiction, comics, film, sculpture, and children’s culture. The analyses of these “haunted texts,” consider how their retellings relate to earlier versions of the mythical theme, including their ancient precedents by Homer and Vergil, but also to post-classical receptions of underworld narratives by authors such as Dante, Ezra Pound, and Joseph Conrad.”

You are all most welcome to join us next Wednesday evening for what promises to be a fascinating presentation.

Conference and Exhibition, “Philo-xeni Archaiologia”

Last Thursday and Friday, October 18 and 19, the Institute took part in a conference – organized by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture to mark the European Year of Cultural Heritage, 2018 – entitled, “Philo-xeni Archaiologia. Foreign Archaeological Schools and Institutes in Greece”. The conference had three themes: (1) The beginnings of the institution of Foreign Archaeological Schools and the first archaeological missions in Greece; (2) Foreign Archaeological Schools today. Contribution and innovation in the area of research and education; and (3) Foreign Archaeological Schools and Society.

The Canadian Institute contributed a paper relating to the third topic, prepared by the Institute’s Interim Director, Professor Brendan Burke, and entitled “The Canadian Institute in Greece: Social and Cultural Activities that Engage with the Past and the Present”. Since Professor Burke was unable to be present in Athens for the conference I presented his paper, which was well received by the good-sized audience in the auditorium of the Acropolis Museum. The programme of the conference can be seen here: www.culture.gr/DocLib/ΠΡΟΓΡΑΜΜΑ ΣΥΝΕΔΡΙΟΥ.pdf

The Ministry also organized a photographic exhibition to accompany the conference, and this opened on Thursday evening, October 18, in the Fethiye Mosque in the Roman Agora of Athens. A number of the Institute’s field projects contributed material for the exhibition, and some photos of the exhibition, focusing on the Institute’s contribution, can be seen in an album on the Institute’s facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/pg/The-Canadian-Institute-in-Greece-173666819462/photos/?tab=album&album_id=10156673622034463.

Warm thanks to our colleagues in the Ministry for organising these events showcasing the work of the Foreign Archaeological Schools and Institutes.

Jonathan Tomlinson

Assistant Director

Tuesday, October 23, 2018

Tuesday, October 16, 2018

Friday, October 12, 2018

Euripides' Hippolytus and Eros as a Killer Virus

“In 430-29 B.C. a plague devastated the Athenian population. Pericles, the statesman, died of it; Thucydides, our main historical witness, caught it but survived. In 428 Euripides presented his Hippolytus and won the tragic prize. In the play Aphrodite decides to kill Hippolytus by making his young stepmother Phaedra fall in love with him because he rejects her godhead. For the Greeks Eros (Love) was a madness that first attacked the eyes before assailing the mind. In both Thucydides’ account and Euripides’ play, the main recurring thematic term is nosos, disease. Of the plague some believed that it had a divine cause, others a natural explanation. The same division of opinions is expressed by the chorus of women in Hippolytus about Phaedra’s illness. Similarly, Aphrodite can be viewed in two ways; 1) as a vindictive deity; 2) as a force of nature in the form of Eros. I shall treat Eros metaphorically as a virus. Although only Phaedra suffers the full effects of Eros’ madness, the contagion spreads by means of Phaedra’s nurse, her main caregiver, and deranges the minds of the other characters. The primary visual image of Hippolytus is Phaedra’s sick-bed which morphs into the bier on which the dead queen is laid out. As a piece of theatre the bed/bier has a numinous existence that is as vital as that of the human characters.”

You are all most welcome to join us next Wednesday evening for what promises to be a most interesting presentation.

Jonathan Tomlinson

Assistant Director

Tuesday, October 9, 2018

Thursday, October 4, 2018

David Jordan (13-2-1942 - 9-9-2018), former Director of the Canadian Institute

The passing of David Jordan is a great loss to the Canadian Institute in Greece (CIG). David served as the Director of the Canadian Archaeological Institute at Athens, the predecessor of CIG, from 1996 to 2000, during some of its most difficult years when its continuing existence was at stake. As in everything else he did, he performed this task selflessly, efficiently, and successfully.

His passing is also a great loss to scholarship. A commanding authority on ancient magic and Greek curse tablets, he traveled widely in the scholarly world, and his opinion was regularly sought on a wide variety of topics in epigraphy, philology, and ancient religion. He possessed a rare and special talent, a quintessential gift, simultaneously to read and interpret the most difficult of ancient Greek epigraphical writing, scratchings on lead curse tablets. With very apparent ease ... I often watched him in action ... he brought order to chaos, producing wholly convincing readings from the most desperate texts. In all his scholarship he was a perfectionist; his research was meticulous and thorough, his arguments were balanced and cogent, and his obvious mastery of his subject, a mastery sans pareil, was everywhere in evidence. Because of this pursuit of excellence he did not publish nearly so much as his friends and colleagues would wish; his extremely high standards would not allow him to let anything go to press until he had solved every problem and examined, verified, and approved every detail. His exceeding care reminded me of descriptions of the method of composition of one of his favorite authors, Virgil, about whose writings we corresponded on a number of occasions.

The passing of David is most of all a tremendous loss to his many friends; we shall all miss him greatly. I first met him when we were both members of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens in the late ‘60s. We had much in common, a love of epigraphy, a love of Greece, and a love of the convivial vibrant life of modern Athens with its so many attachments to the ancient city. His accent and manners were those of a gracious southerner, a gentleman ... he was born in Georgia. He was engaging in conversation and good natured in disposition. He was generous in sharing his knowledge, the most generous scholar I have known. I cannot count the number of times he helped me ... no, I have a computer, I can count some of them: 227 citations among the curse tablets in PAA, and I have not counted elsewhere in Attic epigraphy, topography, and prosopography, to say nothing of the unrecorded number of times he saved me from error.

An epitome of our friendship may be found in our sharing of the organization and presentation of the conference Lettered Attica at the Canadian Institute on March 8, 2000. “Sharing” is hardly the correct word, as the idea of the conference was totally David's and, typically, he did the majority of the work. The papers were published 3 years later as volume #3 in the Institute’s series, “Lettered Attica” after the skillful editing and beautiful typesetting of our mutual friend of many years, Philippa Matheson.

David was most loyal and unstinting in his help to all his friends. Unfortunately that virtue was not always reciprocated and for no apparent reason he was denied tenure at two universities in the US, after which he returned to Greece, where a 3-year interim appointment as a librarian, a position most congenial to David, a bibliophile, was not made permanent. These setbacks were great personal disappointments to David, but the loss to these institutions was the Canadian Institute’s gain, for he was in Athens and free to assume the directorship of the Institute when it most needed a person of his character, administrative ability, and academic stature.

A philhellene par excellence. David was a lover of both ancient and modern Greece, and it was here in Athens that he lived the majority of his life, and it is here that he died.

Ave atque Vale. STTL.

John Traill

University of Toronto